The centrepiece of the opening ceremony at this summer’s London Olympics will be the lighting of the flame at the start of the Games. The honour of bearing the torch on the last leg of its long journey will probably go to a household name from the sporting world, but at the 1948 London Olympics it was carried into Wembley Stadium by an unknown Cambridge athlete — John Mark (East 1939-44).

The centrepiece of the opening ceremony at this summer’s London Olympics will be the lighting of the flame at the start of the Games. The honour of bearing the torch on the last leg of its long journey will probably go to a household name from the sporting world, but at the 1948 London Olympics it was carried into Wembley Stadium by an unknown Cambridge athlete — John Mark (East 1939-44).

Contrary to what most people think, the carrying of the torch from Olympia to the host venue is not a throwback to ancient times. It was a creation of the Nazis for the 1936 Berlin Olympics (although there had been a lit cauldron at the 1928 and 1932 Games) to underline the connection between classical Greece and their Aryan ideal. When the Olympics resumed in 1948, the organisers decided to retain the idea.

In the weeks before the Games got under way there was considerable speculation as to who would get the honour of running the last leg into the arena. Favourites included the outstanding middle-distance runner Sydney Wooderson and the dashing Duke of Edinburgh, who had married the then Princess Elizabeth the previous year.

But the organisers already had other plans. They wanted someone who encapsulated the ideal of Greek god and Wooderson — bespectacled and only 5’6″ tall — did not. So in January 1948, six months before the opening ceremony, they secretly approached Mark, a blond-haired 22-year-old student.

Mark had impressive sporting credentials. At Cranleigh he had won his colours at all main sports, and in 1947 was president of the Cambridge University Athletics Club and had also represented Great Britain at the 400m. He was good enough to be named in the list of Olympic probables for the 400m later that year, but he struggled with fitness issues and his form fell away.

Years later, Harold Abrahams, the Olympic hero featured in Chariots of Fire who was on the organising committee, explained the decision was all about Mark’s looks. “He fitted perfectly the image of an Adonis running a torch up Mount Olympus. Wooderson did not even enter our minds. He was such a frail man and, believe me, carrying the Olympic torch on that last lap with the arm extended took enormous strength. John Mark carried it out to perfection.”

That was endorsed by Sir Roger Bannister, another 1948 Olympic possible who missed out. “It was a controversial selection because there were some great British runners. But he was chosen for his good looks … he was 6’1″ and well built.” The torch relay organiser later revealed the thing that had tipped the decision in Mark’s favour was that he was blond.

If Mark was not a household name, he was well known enough to the Oxbridge-dominated organising committee as he had captained Cambridge in the Varsity athletics meeting in 1947. He was also a superb all-round sportsman — he had earned his colours in all three major sports at Cranleigh — and but for a shoulder which kept dislocating would have been a real contender for a rugby Blue. In the autumn of 1947 he moved from Cambridge to St Mary’s College, London.

In the months before the Games, Mark regularly practised in secret. “A white Rolls began to turn up at St Mary’s to take him to the stadium and back,” one contemporary recalled. “He wouldn’t tell anyone what was going on but when it happened and the other students found out they were livid. When they saw him they used to light their cigarette lighter and run round him in a circle. When they said he looked like a Greek god it was right. He did.”

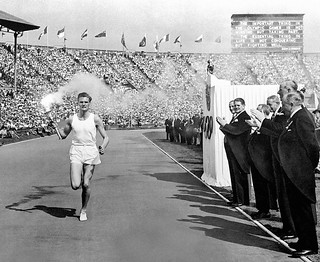

On July 29, Wembley was packed for the opening ceremony. After all the competing athletes had entered the stadium and the speeches had been made, 7000 pigeons were released and off-stage a 21-gun salute sounded.

Then at exactly 4.30pm came what the Times described as the most dramatic event of all — the arrival of the torch. As Mark entered Wembley a roar erupted from the stands, and no sooner had he started his lap of the stadium than many of the athletes gathered in the middle of the track broke ranks and spilt over onto the cinder running track. “This fine and well-chosen athlete performed his task to the manner born,” the paper noted.

“The flame was white against the golden light of the late afternoon,” the Guardian wrote, “and it burned with the resolution of an incendiary bomb. [Mark] began to make his way round, leaving a trail of white heat on the shale surface, running with a perfection of style not easily attained when one arm must be still.”

The Rt Hon Philip Noel-Baker, wrote in the preface to the official 1948 report: “No one who saw it will forget that thrilling spectacle. Tall and handsome like a young Greek god, [Mark] stood for a moment in the sunshine, then ran in perfect rhythm round the track, saluted again and lit the flame in the bowl where, day and night, it burned until the Games were done.”

Fanny Blankers-Koen, who won four gold medals at the Games, said: “When the athlete carrying the torch entered the stadium every woman swooned. He was a magnificent specimen of manhood. I tried to arrange a rendezvous with him after I had won my four gold in medals, but I was told he was too shy to meet me. What a pity!”

Not everyone was swept up in the moment. As Mark appeared it was claimed the Queen (subsequently the Queen Mother) was overheard saying: “Dear me, what a pity they did not get that dear little Sydney [Wooderson] to do it.”

No sooner had Mark completed his task than he happily slipped back into anonymity. An intensely private man, he refused interviews, and until the end of his life was very reluctant to discuss his moment of fame. In his obituary in the Cranleighan it was said he received approaches from several film companies in the weeks after the Games which he politely declined.

Among his friends, however, he was still able to have his leg pulled. Mark played OC rugby on and off for several years, and on one tour two friends set light to a fat rolled-up newspaper that they thought made a good Olympic flame and made him run through the pub giving wild shouts if encouragement.

Norman Gillier, a Daily Express journalist who approached him years later for an interview, recalled: “He was mortified that I had broken into his peaceful world, where he was very content being out of the spotlight. ‘I’m terribly sorry but I do not give interviews to the press,’ he told me in a cutglass Oxbridge accent. ‘All I want to say is that it was the proudest moment of my life to be chosen to light the Olympic flame, and I will never ever forget the day I carried the torch around the Wembley track.”‘

Mark, who joined the navy after qualifying as a doctor, went on to become a much admired rural GP in Liss in Hampshire where he had three children before his first wife died, although he did subsequently remarry. He died at the age of 66 after suffering a stroke while on holiday in the USA in 1991.