As the summer term of 1914 drifted to a close, it seemed pretty much as those that preceded it. The weather was mixed – a warm June had given way to a damp July – cricket was played most afternoons, and until the final few days the escalating crisis sparked by the assassination of Franz Ferdinand at the end of June did not register in the consciousness of many.

The annual old boys reunion in May had been well attended and talk was of the newly-acquired 13-acre field which was being prepared for opening the following year to mark the School’s Golden Jubilee. Speech Day on July 9 was also uneventful, although there was satisfaction expressed that the Officer Training Corp had grown in two years from 80 to 151. The senior prefect – and captain of cricket – John Brice-Smith made a short speech. Fourteen months later he was died of his wounds in Belgium; four of the side who played in the final 1st XI match that summer were killed in the war.

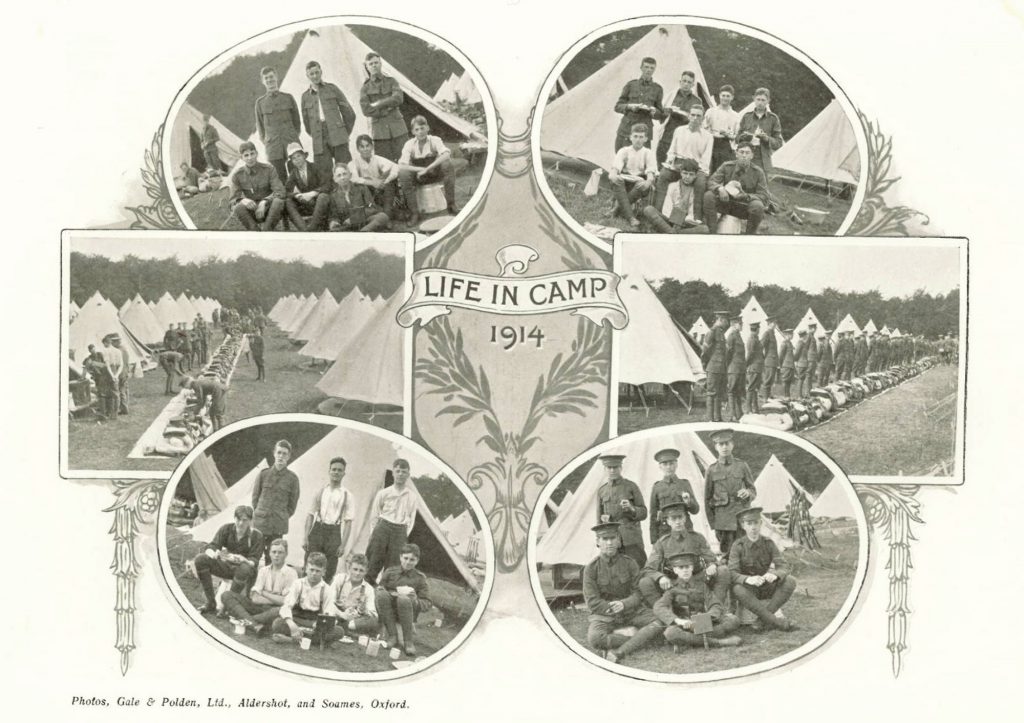

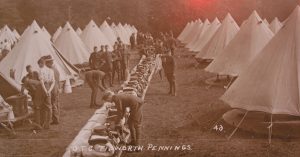

On July 27, two days before the school broke up, 92 OTC cadets and officers left Cranleigh for the annual camp at Tidworth on Salisbury Plain. Along with Epsom College, they were the first to arrive. Almost 3000 boys from 40 schools were divided into battalions of around 800. The Times report gave hints that camp life was not exactly onerous as “practically all fatigue work is done by orderlies”.

The term ended on July 29 and most boys headed home with no thoughts other than the holidays. They walked down to the Cranleigh station to catch a train to Guildford; their bags followed in the next few days. “The clouds of war were gathering,” wrote Geoffrey Bateman (2 North 1919), “but I think most of us regarded the trouble in Serbia as just a third Balkan war. But by the end of term the situation looked more serious”.

At Tidworth, life was fairly routine, although the talk all centred on the increasing likelihood of war. On the Saturday night Cranleigh drew with Rossall 3-3 in a game of football, beating St John’s Leatherhead the following evening. “On Sunday, things began to look serious,”wrote a boy from Gresham’s (who were in the same battalion as Cranleigh). “Sunday morning broke in a torrential downpour and news that the fleet was mobilising.”

On Bank Holiday Monday (August 3) the order was given for the cadets to strike camp three days early. The staff officers had to peddle round on bicycles barking out the orders as the previous day their horses had been requisitioned. Arthur Wilson, who left Cranleigh at the end of the term but attended the camp, said that when war was declared “we all thought it would be over in a couple of months”.

That evening, Private Leonard Arnold won the bugling competition “after a tremendously close contest”. It was his last contribution to Cranleigh life. He joined up later in the year, was invalided out in 1915, rejoined in 1916 and was killed in action in India in 1919.

By the Tuesday morning almost all the regular soldiers had disappeared and the cadets were left to make their way home as best they could. The trains were “deranged” because of many lines being requisitioned to get troops and equipment to the south coast. “Eventually we did move off,” the Cranleighan reported. “Some by train, some by motor bikes and some, we believe, seen disappearing into the morning mist of the plain on foot.”

Wilson was one of a handful sent back to Cranleigh to guard the armoury, even though he was by now an old boy. By the time the School reassembled on September 18 more than 200 Old Cranleighans had enlisted, and three masters were also in the forces. Two Cranleighans – Captain Harold Bass and Major Percy Maclear – had already been killed although Bass was listed as missing for almost another year while Maclear’s death was not announced until early October.

On the first Sunday of term the Headmaster gave a sermon in chapel which began: “Strange things have been happening since we were here last …”