On April 26 1915, Harold Haile ‘Tertius’ Last (East 1905) died at the Queen Alexandra Hospital in London from injuries received in Belgium the previous month. He was 22 and was the tenth Old Cranleighan to have died in the nine months of the war to that point; he was buried soon after with full military honours at the family’s home town of Clacton-on-Sea

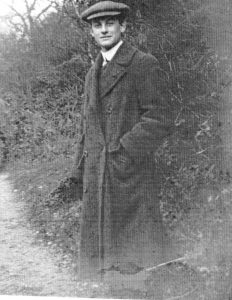

Last, who was at Cranleigh from 1903 to 1905, was the third of seven brothers, four of whom went to Cranleigh; as the third son he was nicknamed and known thereafter to the family as Tertius. On leaving, he became a draper’s assistant but he had joined the reserve of the Honourable Artillery Company earlier in 1914 as the political situation deteriorated. As a result, when war broke out in August he was immediately called up. After little more than a month’s training he headed to France as part of the 1st Battalion of the HAC.

Last first saw action in November 1914 when his battalion spent a week in the trenches near La Cloutuse and by the end of the month he was near Ypres. For the next three months he was in and out of the trenches and rarely spent a week in the same place.

Last kept a regular diary and it has been passed down through the family so we know his exact movements. On February 17 he wrote: “Morning comes and we find the front of our trench littered with dead English soldiers, the first I have seen. Our trench is only some sandbags against a hedge.” Six days later: “Heavy fog this morning so I go for a walk round the back of the old French trenches and see some more ghastly corpses.”

Sleep was hard to come by, partly because of discomfort but also as a result of the bitter cold. On February 24 he spent the night “in a little hole under the stairs” while it snowed outside. The next night he was billeted in a small café but so many men were there that he could not straighten his legs. That he was suffering from diarrhoea only made things more uncomfortable.

On March 1 he went on a route march but “a blizzard came on, terrible mud and blinding snow.” After four days in reserve he went into the front line on the evening of March 5: “We enter the trenches under a perfect hail of bullets; we escaped wonderfully.”

Although only there a day, it was a difficult one. “This trench is a rotten one,” he wrote. “It rains all day, we get shelled a trifle in the afternoon and the East Surrey billet gets burnt down and I had the Hiperscope that I was observing through shot and the glass cut my face while the bullet narrowly missed my head. We are relieved about 7.30 and get away with very few bullets at all.”

That was the routine; a day or two in the front line and then the same time behind, catching up on sleep and food before returning. But his diary makes clear the excitement at the prospect of engaging the Germans. A planned offensive on March 13 was delayed by the weather. “We are waiting for the fog to clear when we hope to have some sport. All last night we spent making good fire positions. [At] 2.30 the bombardment commenced and lasted until 4.30 when the Worst. & Wilts. attacked while we gained superiority of fire, firing each between 100 & 200 rounds. The shelling was awful. Granny [a massive German field gun that could be heard on the English coast] barked seven times her limit and every gun for miles fired. The Worst. took their trench but were unfortunately shelled out by our own artillery (the Germans picked up our wounded). Several of our shells fell short into our trench. During the evening we were not allowed to fire a shot. The Germans fired grenades at us, we had two killed and three casualties and the base not relieved and had to stand to nearly all night.”

They were eventually relieved two days later, marching for three hours to relative calm six miles behind the front line, arriving exhausted at 3am. After six days rest they were sent back to St Eloe “to trenches which we must hold with the utmost vigilance”. On arrival he was fed up to find “our trench is just a pile of sandbags in front of the mound” with the German line 60 yards away.

On March 24 he wrote: “Had a fairly quiet day. It rained hard all night. This morning [Lance Corporal Ernest] Buckney was shot, he died later. As I write this there is the most glorious sunset over Mt Kemmel the sky is one sheet of gold and then on our left is a heap of ruins called St Eloe. One wonders why this awful war is waged. In front of our trench are dead bodies galore. Our wine is absolutely useless, we have the prospect of lasting another 24 hours on our water bottles.”

The next morning they were relived and marched back to Dickebusch. “We all sleep in the cellars full of lice and everything else that is nice. We sleep very well in our wet clothes all of us.

This morning we have a wash and shave and a good feed.”

In the afternoon of March 25 he went foraging in a ruined house and while out he was seriously injured in the neck when a shrapnel shell burst over his head. Remarkably given the seriousness of his injury, he continued to keep his diary. “ I was taken to the dressing station where I was found to have paralised legs.”

The next day he was carried on a stretcher into Dickebusch, a journey of about a mile. “I can tell you the road was not soft or the men’s shoulders easy… I was put into an ambulance and am taken to a dressing station for the night. Here I remained until 10 o’clock when I was taken in a motor ambulance to Bailleul. Here I was redressed and remained in a dismal ward for some hours.”

On March 27 he made his last diary entry. “Today at 10 o’clock I was packed into an ambulance & brought to the Casino (No 13 General Hospital) Boulogne, where I shall work out my salvation.”

It seems likely that Last would have died there but for his 25-year-old sister Dorothy. Last’s niece explained. “Dorothy may have been a bit psychic as she had a premonition that Tertius was in trouble in March 1915 and bullied her way into getting a passage across to Belgium and found him paralysed from the neck down. She brought him home to die.” Last seems to have left the field hospital on April 16 and arrived in London the following day. He died nine days later.

His younger brother, Leo (House 1906), was killed on July 1, 1916. It was his 20th birthday. Letters he wrote to his sister are still in the possession of the family. In the last, written to Dorothy on June 28, 1916, he finished: “I cannot write any more, Old Girl. I am very sorry but I seem a bit jumbled up in myself, but I want you to pray for me especially in the days that are coming, that I may do my duty as I ought.”

Leo was one of 660 men of ‘C’ Company of the 19th Battalion of the Middlesex Regiment who went into the line early in the morning on the first day of the Battle of the Somme. Only 72 attended roll-call that evening.