At a time much of the talk is how people – especially younger ones – are becoming increasingly disillusioned with politics and politicians, it is worth remembering that state of mind is nothing new.

In 1973 as trade union militancy grew and strikes were called aimed at bringing down the Conservative government of Edward Heath (which they did in February 1974) a number of organisations were formed with the aim of stepping in to encourage and support what would have been a right-wing army coup in the event the elected government was toppled by communist agitators, a body indistinguishable to many from the official Labour party.

One of the most extreme of these was the Middle Class Volunteer Reserve which was the brainchild of Rupert Ross Goding (East 1915).

Goding (who was registered on entry at Cranleigh and known as as “Gooding”) served in both wars although was dismissed from the Royal Flying Corps after being court martialled in 1917, rejoining in 1938 as a flying officer and eventually becoming a wing commander.

He had been stirred into action after losing £3000 when the Labour government of Harold Wilson had re-nationalised the steel industry in 1967. Deciding that the vast majority of the country was middle-class and largely unrepresented, he formed what was initially known as the Middle Class Junta, what was in effect a private army. However this may sound now, it resonated with a small section of the population and he attracted members and subscriptions.

“As peaceful as we are,” he stated, “our members are ex soliders, sailors and airmen and well-trained me who would rise if called upon by the legitimate government of this country.”

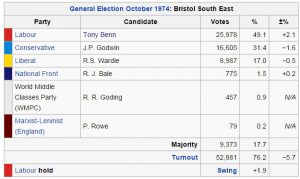

Goding’s campaign came to a head at the October 1974 election when he stood under the MCVR banner in Bristol South East. He picked that constituency as it was the seat of Tony Benn, the minister who he believed had robbed him of his investment seven years earlier and a strident left-winger.

On the day of the poll he wrote to Marc van Hasselt, then Cranleigh’s headmaster, offering to come and speak “as attacking the Labour party is very popular with VIth formers” and concluded by admitting that he did not expect to topple Benn “but as long as I don’t lose my deposit I shall be quite happy”. His offer was politely declined.

He was to be disappointed in the election as well. Benn slightly increased his majority while Goding came fifth out of six candidates with 457 votes. He might have got a slither of satisfaction that he polled more than the official Communist candidate.

He also wrote to David Loveday, who had been headmaster from 1931 to 1954, and Loveday forwarded that letter to van Hasselt with a note saying he had read it “with sympathy and interest … I applaud his venom”.

Undaunted, Goding vowed to “redouble my efforts at the next general election”. It was not to be. He died at his Somerset home in December 1977 aged 79.