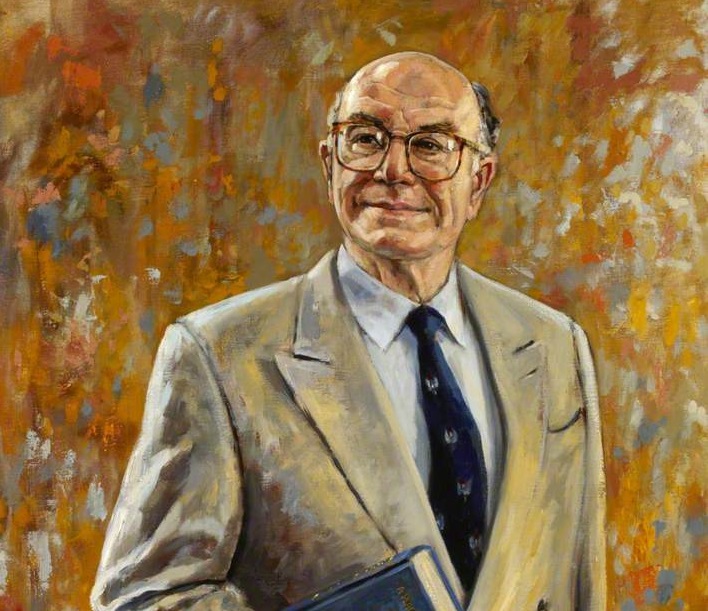

It is with great sadness we have learned that David Emms, who was Cranleigh’s headmaster between 1960 and 1970, died on December 21. He was 90.

It is with great sadness we have learned that David Emms, who was Cranleigh’s headmaster between 1960 and 1970, died on December 21. He was 90.

After Tonbridge and then after serving with the Royal Artillery from 1943 to 1947, he studied modern languages at Oxford. He graduated in 1950 and in the same year married Pam, who was his lifelong companion and a vital support throughout his career. They had four children. A good rugby player, he won Blues in 1949 and 1950, and went on to represent Northampton, Eastern Counties and the Barbarians.

In 1951 he became an assistant master at Uppingham, going on to head its modern languages department, before being appointed as Cranleigh’s headmaster in 1960. He was 35.

He arrived at a School at its lowest ebb following the resignation of Henry March as headmaster in 1959. While Emms was aware there were problems, the scale of them came as a shock. “The first two years were quite terrible,” he said. “It’s hard to stress how grim it was. I was continually surprised. But I knew I had a job to do, particularly with the prep schools, and I was always optimistic.” A decade later, as he prepared to leave, he said he had inherited “a temporarily unhappy public school, a school in crisis”.

He very quickly clamped down on discipline and worked tirelessly, and successfully, to restore the School’s reputation. In an era of social upheaval, he made changes to bring Cranleigh into tune with the times. He ended fagging and corporal punishment, brought in the first girls, ended compulsory participation in the CCF as well as compulsory weekday chapel, and introduced casual clothing at weekends.

Even though he inherited a full school, the academic standards were also at a low, with the common entrance pass rate slipping below 50%. At his first assembly he told the boys he was passionately in favour of hard work and that while he loved games too “heaven forbid we should send forth a series of muscular but narrow-minded athletes with nothing but the Playfair Annual or Wisdento comfort them when their boots are finally and conclusively hung up”. Gradually he introduced recognition for work. One of his initiatives was the introduction of the Academic Tie (until then the only ties had been ones connected with sporting achievements), the work cup and Lower VIth exams. Initially through hard work with the feeder schools (“I was relentless in visiting prep schools and I hope I encouraged the nicer boys to come”) the calibre of entrants began to rise as did the common entrance pass level. By the mid 1960s Cranleigh was able to turn away those who a decade earlier it would have gratefully accepted although Emms said he “always made exceptions for the OC element and allowed a brother or a son in even if they were six or seven percent below the passmark as it was our idea to make Cranleigh a family school”.

For much of his tenure, public schools were under constant attack as being an elitist anachronism. Emms responded by involving Cranleigh in the local community and making sure the boys were aware of the privileged opportunity they were being given. As inflation crept up and the economy wobbled, Emms said “it was a threat through tax, so we made the fees the most expensive in the country. For a year or so we were ahead of Eton and everyone else. My philosophy was that anything that is priced so high must be good.”

While he had a reputation as a strict disciplinarian, he also allowed boys greater freedom to express themselves. In 1964, in the face of opposition from his own common room, he allowed the drama department to stage West Side Story, at the time an almost revolutionary move. He encouraged irreverent end-of-term reviews while regular exeats were also introduced in the summer of 1967. “We were the first school in the country to do so,” Emms said, “with the aim of getting boys to see their families and their girlfriends more often.” Parents, for a century expected to do little other than pay the fees and drop and pick up their children, were also encouraged to become more involved. “I couldn’t stand it and said there would be parent-teacher meetings. A master came and said: ‘I can’t come to any of your parent teacher meetings as I have other work to do.’ I told him he better find another school.”

The governors also supported an ambitious building programme which he pushed for from the outset, including a complete overhaul of the houses’ accommodation. He oversaw the opening of the seventh boarding house, Cubitt, in 1961 and in 1965 1 North moved into a new purpose-built home.

As Emms approached a decade at the helm, Cranleigh’s future was secure and its reputation burgeoning. Still only 44 and highly regarded, it was expected that Emms would be poached by one of the major schools in the future. And so the governors were caught completely unawares when in July 1969 he told them he was leaving to take charge of Sherborne. He had rejected Sherborne’s first approach but was concerned about his future and so decided to take an improved offer. “I was rather afraid I would be turned out of Cranleigh,” he said. “We should have stayed but I had a terrible feeling that people would get fed up with me. Our last years at Cranleigh were the happiest of our lives. The school was going very well.” Asked as he left what he felt his greatest achievement was, he replied: “I am most content with the fact that the vast majority of boys in 1970 are happy whereas in 1960 many were extremely unhappy.”

Sadly, his time at Sherborne was not happy. The school needed reform but he faced a hostile common room and, unlike Cranleigh, he did not enjoy the support of the governors and he left after four years. In 1975 he was made Master of Dulwich College where he remained until 1986. In 1984 he was chairman of the Headmasters’ Conference. In retirement he remained very busy with a number of positions and governorships, and in 1995 he was awarded the OBE.

He maintained close links with, and a deep affection for, Cranleigh. In the 1990s a new maths block was named after him, something that amused him as he admitted the subject was one of his weakest. In 2009 he opened the £10 million Emms Centre. “This was one of the great honours of my life” he said. “Pam and I thought it would be a small classroom block and it turned out to be a remarkable building”.

Such an influential and important figure in Cranleigh’s history deserved nothing less.

Mike Payne, who Emms appointed in 1967 and who remained in close touch, said: “He was a great man in every sense. He filled rooms with his presence. He was my idea of a leader, and he had a warmth and capacity for friendship which marked him out as very special. No-one has taken greater pride in Cranleigh than David. I feel proud to have known him.”