Ninety years ago this month the country was paralysed for nine days by a General Strike, when almost two million worker, mainly in transport and heavy industries, stopped work in support of more than a million coal miners who were facing wage reductions and deteriorating working conditions.

For the then cosseted schoolboys at Cranleigh the impact was minimal, although it brought glimpses of the reality of the outside world into School life. There was little interruption to daily routine, and food and milk was plentiful, unlike in the cities where there were shortages.

To most of the public the biggest impact was the cessation of public transport. On May 4, the first day of the strike, there were almost no trains or busses, and roads into London were congested “with all types of vehicles, and charabancs left towns in West Surrey heading for London”. However, the breakdown of law and order feared by many and almost enthusiastically predicted by the more sensational newspapers failed to materialise.

The lack of trains contributed to a virtual suspension of the postal service, and this did affect Cranleigh’s pupils as letters provided their only regular contact with the wider world. Perhaps more importantly the food parcels many received from families not only helped supplement the often dire meals provided by the School but also gave them items with which they could barter with their coleagues.

Most newspapers ceased to appear on May 5 as the print unions joined the strike, and the only sources of news were the British Gazette, which was essentially a government-run propaganda sheet, and the fledgling BBC. One boy recalled that they assembled in Hall every day where a master read the Gazette to them. “That aside,” he said, “the Strike made no practical difference to our lives.”

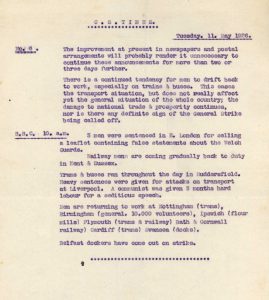

At Cranleigh John Purvis produced a one-page news-sheet (the Cranleigh School News) on a device known as a jelly duplicator, the end result pinned up on noticeboards. The first issue came out on May 6, with the last edition published on May 11 by which time the strike was petering out. There was a rival – the Cranleigh Evening News – which was typed by boys and, again, put on noticeboards. “These gave the important news from the wireless bulletins,” reported The Cranleighan, “when we were very largely cut off.”

The Surrey Advertiser – at the time published on Wednesday and Saturday – continued to appear but with fewer pages as the proprietors explained they wished to conserve paper as they did not know how long the strike would last.

Within a two or three days a recruiting centre was established in the Village where men could enrol to help maintain essential services. Like other such centres in the area, they were deluged with volunteers, many exited at the prospect of being able to drive a bus or train.

By the start of the second week the strike was starting to crumble and life quickly returned to normal. On May 12, the TUC ended the General Strike, although the coal miners continued their industrial action until the end of the year.