Sir Gordon Brunton (East 1936) died on May 30 at the age of 95.

Born into a poor family in London, his mother left his father when Gordon was five, taking her child with her, and in 1935 Gordon was sent to Cranleigh. The Times noted “he found the experience of boarding traumatic” and he left at the end of his first year. That he broke his leg in his first term when hit by a car crossing the road cannot have helped his enjoyment, although he subsequently sent his two sons Colin (1&4 South 1966) and Mark (Loveday 1990) to Cranleigh. He subsequently went to the London School of Economics and when they were evacuated to Cambridge he went with them.

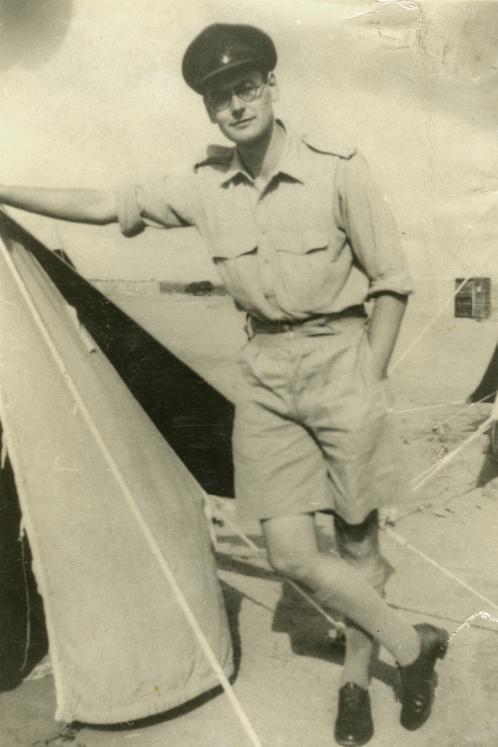

Before he could complete his degree he was commissioned into the Royal Artillery in 1940, serving as a captain in the Indian Army where he fought in the Burma campaign. After the War he was posted to the British Military Government in Hamburg and Dusseldorf to work on reconstruction.

There Brunton met Nadine Sohr, a Belgian nurse, whom he married in 1946. They had three children. After being demobbed he returned to England where he found work selling classified advertising space to small businesses. He rose through the ranks to become managing director of the company, before joining Thomson newspapers in 1961.

Within months, Brunton found himself in a difficult situation. Thomson had purchased the Illustrated London News which had commissioned and published a series of innocent portraits of Prince Philip, Princess Margaret, Lord Snowdon and about 30 other royal family members. They had been drawn by Stephen Ward, the osteopath who became a central figure in the 1963 Profumo scandal. During the trial, Ward exhibited the portraits at a London gallery.

“After representations from ‘the highest level’, which he promised never to reveal, Brunton sent an executive to the gallery to buy every royal portrait and load them into a taxi,” The Times reported. “The portraits lay in a vault for 30 years until the Illustrated London News changed hands and the new owner put them up for sale.”

Brunton’s entrepreneurial flair was recognised by Thomson and he was given scope to move away from newspapers. Despite fierce opposition from Thomson’s accountants, Brunton engineered the purchase of Riviera Holidays and Universal Sky Tours, which owned three second-hand aircraft, trading as Britannia Airways. The business, as Thomson Travel, soon made worthwhile profits, but Brunton also discovered the risk of airline ownership. In 1966 one of the Britannias crashed in fog at Ljubljana airport in what was then Yugoslavia, killing more than 80 and leaving 30 badly burnt. Brunton flew to the site to organise the rescue and bring bodies back. “It was like a charnel house,” he said. “I had been through the war and was not unfamiliar with death and mutilation, but this was the most horrific experience of my life.”

In 1965 his marriage was dissolved and the following year he married Gillian Kirk. From 1968 Brunton was managing director and chief executive of all Thomson’s publishing and other interests, often acting as the bridge between the proprietor and the management of the businesses below. That placed him in a difficult position in 1979, when Times Newspapers – burdened by frequent production disputes and rising losses – forced a confrontation with print unions which caused the papers to cease publication for almost a year. Although Brunton backed the strategy, he came round to realising the strike had to be settled.

He delivered the message that Thomson was “not prepared to foot the bill any longer” and was accused by more hawkish colleagues of “waving the white flag”. By the time the stoppage ended in November 1979, it had cost £46 million and was seen as a disaster for the company. Another strike in 1980 led to the company being put up for sale and Brunton conducted much of the secret negotiation that followed from his own home. From several bids he chose to do a deal with Rupert Murdoch whom he regarded as tough but straight and committed to preserving both titles, even though Murdoch’s offer was not the largest. Sir Harold Evans, a former editor of The Times and The Sunday Times, said of Brunton: “He is a generous man, but not one to trifle with. He has a habit, when opposed, of lowering his large, domed forehead as if about to charge.”

He delivered the message that Thomson was “not prepared to foot the bill any longer” and was accused by more hawkish colleagues of “waving the white flag”. By the time the stoppage ended in November 1979, it had cost £46 million and was seen as a disaster for the company. Another strike in 1980 led to the company being put up for sale and Brunton conducted much of the secret negotiation that followed from his own home. From several bids he chose to do a deal with Rupert Murdoch whom he regarded as tough but straight and committed to preserving both titles, even though Murdoch’s offer was not the largest. Sir Harold Evans, a former editor of The Times and The Sunday Times, said of Brunton: “He is a generous man, but not one to trifle with. He has a habit, when opposed, of lowering his large, domed forehead as if about to charge.”

Brunton remained chief executive of Thomson’s international and UK arms until 1984, while building a portfolio of other interests. He was flattered to be asked to join the board of Sotherby’s in 1978 – “It was like being asked to join the Guards” – but found its proceedings distinctly unbusinesslike: “If you said. ‘What’s the plan here? How much does it cost? They’d look at you … as if you were farting in church. ”

In 1982 a struggling Sotherby’s asked Brunton to take over as chairman and he immediately produced a highly critical report on the company. “Though affable in manner,” wrote the firm’s historian, “Brunton was capable of charging like a rhinoceros … pursuing his goals with intimidating force.”

Management changes and cost cutting did little to revive the share price and in 1983 he fought off an a bid from two American entrepreneurs who he described as totally unacceptable”, arguing that a firm to much part of the national heritage must remain in British hands. His argument worked but months later Southerby’s was bought by US real estate tycoon Alfred Taubman who replaced Brunton as chairman.

In the 1980s Brunton was also a non-executive director of Cable & Wireless and its subsidiary Mercury Communications, and in later years he was chairman of Galahad Gold. Among many voluntary roles, Brunton was president of the Periodical Publishers Association and the National Advertising Benevolent Society; chairman of the Independent Adoption Service; a member of the Arts Council’s South Bank board and the council of Business in the Community; and a governor of the LSE. was knighted in 1985.

That year he was appointed chairman of the Racing Post –first published in 1986 – and held that position until he resigned in 1997 after the paper was sold to Trinity Mirror. Brough Scott, who was instrumental in the Racing Post‘s launch, said: “Without Sir Gordon Brunton I doubt the Racing Post would have survived. He was quite magnificent and we were incredibly lucky to have someone with his profile in the newspaper world and enthusiasm for racing when we were all so inexperienced.

Another observer wrote of Brunton that he possessed “the gambling streak that goes with enterprise and which, in his case, found another outlet in racehorse owning”. He was a successful breeder at his North Munstead stud in Surrey. His proudest moment on the racetrack was watching his Indian Queen, a rank outsider at 25-1, ridden to victory by Walter Swinburn in the 1991 Ascot Gold Cup. When he was indulging his other great pleasure, steering his motor launch Ocean Victory around the Mediterranean, he would often be on the phone checking how his horses were doing.

Brunton, who died from complications arising from surgery, went knowing that one of his horses, Munstead Star, had come second in the 3.50 at Leicester. His last words to his family were: “That’s fine. Don’t be late for dinner. Goodnight.”