Much will be written in the coming days about those involved in the D-Day landings. Among the 1,449 British combatants who died on June 6th 1944 few stories are quite as sad as that of 24-year-old Private Philip Sargent.

Sargent, who was in 1&4 South, was at Cranleigh from 1934 to 1938, where he shone as an actor, and in his final term he edited The Cranleighan. Jeremy Bliss (West 1938), a friend of Sargent, recalled: “We found ourselves in collaboration as editor and assistant editor of the magazine and between us produced the pacifist issue which caused such disquiet amongst the more military members of staff, although it had the full approval of Max Machin (MCR 1922-1957), who had seen just enough of the 1914-18 war to finish up in a military hospital sickened by the suffering around him, which he felt was a very small sample of the outcome of every battle. Sargent was almost entirely responsible for the editorial.”

On leaving school, Sargent joined a firm of solicitors in Bedford and in January 1941 he was called up. As a conscientious objector and committed pacifist, he opted to join the Bomb Disposal Squad where he remained until June 1943 when he transferred to the Royal Army Medical Corps. He undertook parachute training at the end of July and on August 18th he married Bunty Adams, his fiancée of three years.

Much of the next ten months was spent in camp preparing for D-Day. Like so many of his colleagues, it would be Sargent’s first taste of action.

He was part of 224 Parachute Field Ambulance, Royal Army Medical Corps (6th Airborne Division) who were some of the first to be parachuted into Normandy in the early hours of June 6th. They were part of the advance guard who were dropped at Varaville hours before the beach landings with the aim of taking out the battery of Merville to the south-east of Cabourg, destroy bridges and prevent the arrival of German reinforcements during the landings. The RAMC’s immediate role was to deal with casualties from the drop.

The Dakotas carrying the men took off between 11pm and midnight, making uneventful progress until they crossed the French coast when they were peppered with flak. To add to the pilots’ problems, visibility worsened and many men were dropped several miles from their target, some as far as 8 kms away. It took a number of hours for the disparate groups to find each other, their efforts not helped by mist and the fact the Germans had flooded the area to deter glider landings, which had turned the fields into bogs up to seven feet deep. Some men drowned while much equipment was lost.

The Dakotas carrying the men took off between 11pm and midnight, making uneventful progress until they crossed the French coast when they were peppered with flak. To add to the pilots’ problems, visibility worsened and many men were dropped several miles from their target, some as far as 8 kms away. It took a number of hours for the disparate groups to find each other, their efforts not helped by mist and the fact the Germans had flooded the area to deter glider landings, which had turned the fields into bogs up to seven feet deep. Some men drowned while much equipment was lost.

At around 6.45am, Sargent and a number of others of his section were on their way to Bois de Bavent to try to find the 9th Parachute Battalion when they were hit by a torrent of anti-personnel bombs dropped off target by the Royal Air Force. The diary recalled what other members of the RAMC saw from nearby:

“There was a sound of aero engines, then they heard the soft precise thudding of bombs falling so rapidly it sounded for a moment like an artillery barrage. The sky, by this time coloured by the sunrise, became suddenly overcast as a great pall of dust and smoke rose hundreds of feet in the air. It was a tragic and futile incident, which only increased the bewilderment felt.”

Those caught in the onslaught flung themselves on the ground but they had little cover. “The air was filled with flying fragments of shrapnel and the acrid fumes of explosive. When they got up both sides of the lane were strewn with dead and wounded … Sargent, despite a thorough search, was nowhere to be seen.”

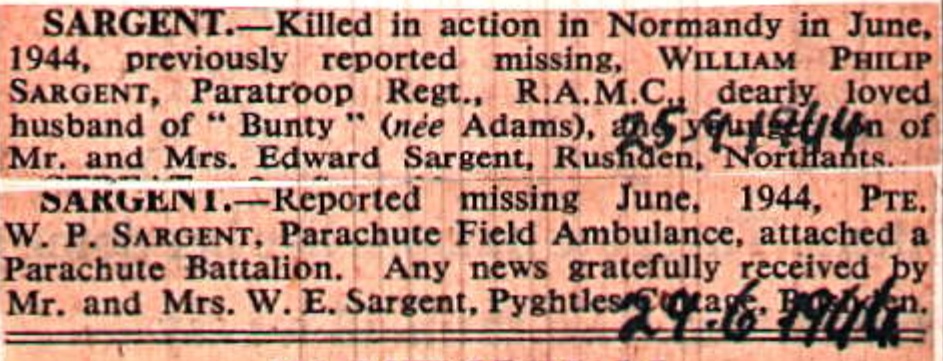

Officially, he was reported missing in action. His parents placed an advertisement in the Times on June 29th asking for any information about his whereabouts. In late September they were told he was presumed dead.

Bliss, writing of his friend 40 years later, said: “That is the final irony, the final crossing of our paths. I now know that we both went to Normandy on D-Day; we were both unarmed. He was on an errand of mercy and died. I was not and survived.”

Seven weeks after the official notification of her husband’s death, Bunty Sargent gave birth to a son, Jonathan William Philip.