On January 24th the Sunday Telegraph carried a full-page article by Charles Richardson on the success of sport at Cranleigh.

Before the pandemic reared its ugly head, Cranleigh School, a towering, neo-gothic institution in the Surrey hills, had started to build a valid case as the country’s best for sport.

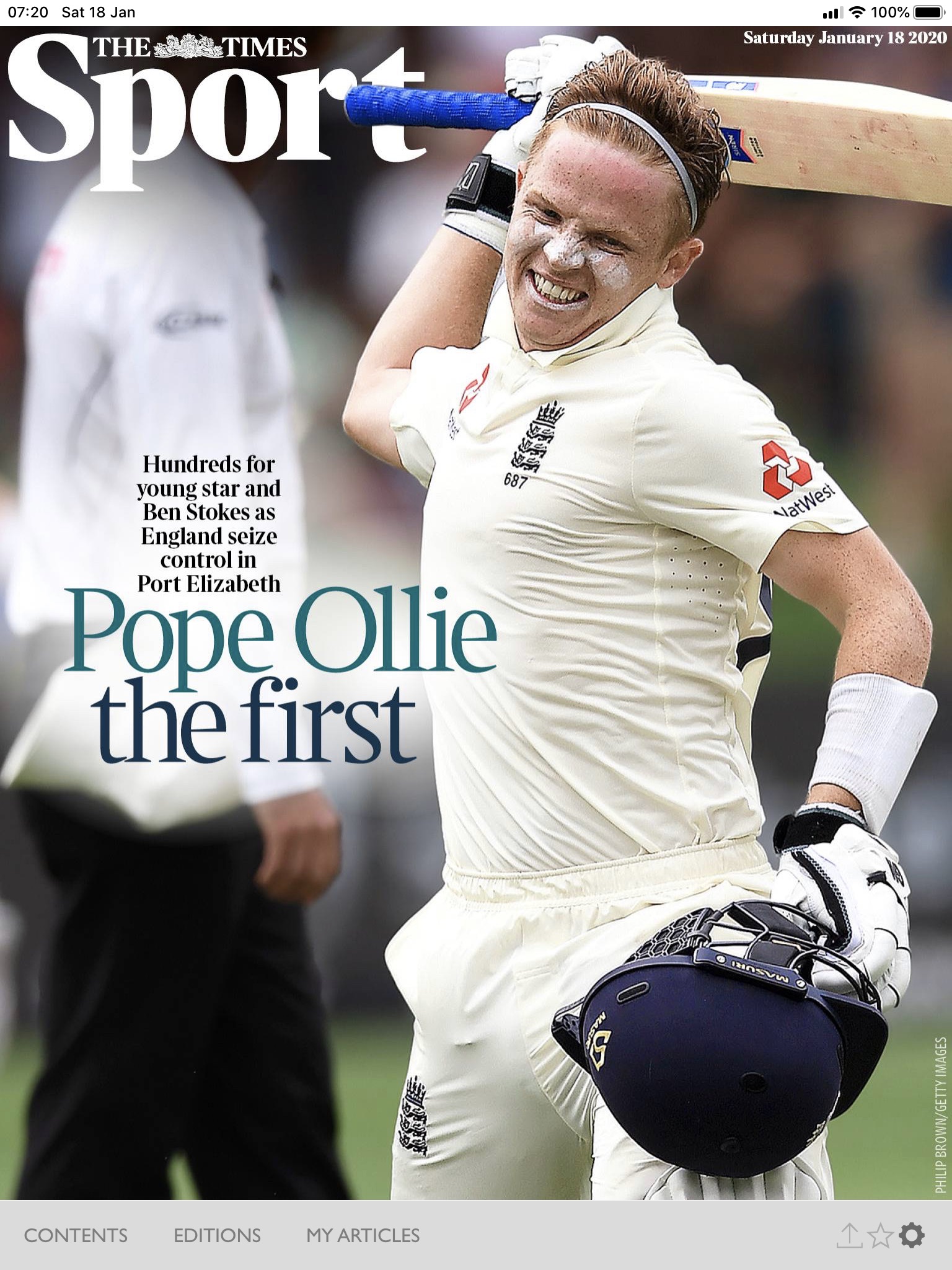

The school has long had a proud record in producing rugby talents – Premiership stalwarts Will Collier and Greg Bateman are alumni, while seven Cranleighans were enrolled in last season’s Harlequins academy squad – but that is just the start. Isabelle Petter represented Team GB at hockey while still at the school, and Ollie Pope, England’s impish batsman, played both hockey and cricket at Cranleigh.

It is Cranleigh’s relatively recent rise to the upper echelons of British school sport – most of its well known sporting alumni are less than 30 years old – as well as its willingness to look after the non-elite, that is most striking. Every pupil plays a team sport at some level, and almost every member of staff coaches one. The school’s reach into the community is notable, too: their groundsmen look after the pastures of the local secondary school, while, in these most testing times, staff have been running activity sessions for key workers’ children during school holidays.

It is Cranleigh’s relatively recent rise to the upper echelons of British school sport – most of its well known sporting alumni are less than 30 years old – as well as its willingness to look after the non-elite, that is most striking. Every pupil plays a team sport at some level, and almost every member of staff coaches one. The school’s reach into the community is notable, too: their groundsmen look after the pastures of the local secondary school, while, in these most testing times, staff have been running activity sessions for key workers’ children during school holidays.

Since the effects of Covid-19, however, the landscape for the school’s sports programme has changed. For instance, this year’s crop of precocious rugby talent will be denied any XVs rugby this season, with hopes even fading for a springtime VIIs season. The question now, is how does a school with such impressive sporting credentials – at elite and non-elite levels – adapt to such restricting circumstances, even with its £40,000-a-year price tag?

The man to answer that question is Andy Houston, the brain behind the school’s rugby success, which includes two unbeaten seasons in the last five years and two victories and a runners-up spot since 2016 at the prestigious Rosslyn Park Sevens tournament. Houston is an alumnus and the school’s director of sport. His philosophy on the current situation for sport – specifically rugby – is simple: it is not a setback. “It was obviously great, over 10 years, getting to the level that we got to,” Houston says. “And if you look at this in the sense of what we cannot do, then it does seem like a setback. But we are looking at this and thinking: ‘We have 420 boys in this school, the vast majority of whom will play rugby. This is our opportunity to really work on skill development and their understanding of the game without the pressure of matches on a Saturday.’

“In this break, either myself or Phil Burgess – our new head of rugby – have coached every single one of those boys. So it doesn’t matter if you’re an A-teamer or a D-teamer, we have what we hope is the best coaching you could possibly get. Some guys who don’t like contact too much have really progressed. They are becoming very talented rugby players and, when they grow, they will be outstanding. But sometimes, with the pressure of matches on a Saturday, and if you’re 14 years old and not very big, rugby can be quite an intimidating game. So, in that sense, I don’t think it’s hindered us. I think people will look back and think, ‘Wow, this has been a real benefit.’ It has changed the psyche of the school a little bit.”

But pupils and alumni of Millfield, Sedbergh and Wellington among others might be feeling hard done by. Their reputation on the sports field precedes them just as much – if not more – than Cranleigh, they count more superstars among their sporting alumni, and their facilities are state of the art. So, why does Cranleigh deserve its lustrous reputation? “The mistake, because we have been so successful in some national tournaments, is to expect that success drives the sports ethos of the school,” explains deputy headmaster Simon Bird. “But it’s the other way around. The sports ethos of the school – participation and enjoyment – is what has led to the competition victories. A lot of other schools do sport very superficially. The top eleven kids in a year group will make a strong A team, but what are these schools doing for the pupils below? Does it all tail away when you get away from the most enthusiastic kids?”

But pupils and alumni of Millfield, Sedbergh and Wellington among others might be feeling hard done by. Their reputation on the sports field precedes them just as much – if not more – than Cranleigh, they count more superstars among their sporting alumni, and their facilities are state of the art. So, why does Cranleigh deserve its lustrous reputation? “The mistake, because we have been so successful in some national tournaments, is to expect that success drives the sports ethos of the school,” explains deputy headmaster Simon Bird. “But it’s the other way around. The sports ethos of the school – participation and enjoyment – is what has led to the competition victories. A lot of other schools do sport very superficially. The top eleven kids in a year group will make a strong A team, but what are these schools doing for the pupils below? Does it all tail away when you get away from the most enthusiastic kids?”

At Cranleigh, it does not. The school’s largest sporting trophy is awarded in hockey, to a player who has not been involved in one of the top sides. In a school of around 650 pupils, a relatively small total in independent school terms, the commitment to fielding three or four teams in every age group across several sports is unusual. “Our whole philosophy is based around participation; people having a go,” says headmaster Martin Reader. “And, at the same time, do your best. If you just want to participate for fun, that’s here for you. But if you want to push to the higher levels, we want to support that.”

At those higher levels, rugby remains Cranleigh’s sporting pièce de resistance. And, while success with the oval ball is no longer the direct remit of Houston, he remains fondly attached. He built Cranleigh up from relative also-rans on the school rugby circuit and turned them into the behemoth that they are today. “It’s really been a mindset change. It’s more that we go to things now with the idea of winning it, rather than just being happy to play in a quarter-final. The kids are much more aspirational,” Houston says of that transformation. “When I first started, there was no strength and conditioning as such. There was a group of four boys: Henry Taylor [Northampton Saints], Harry Elrington [London Irish], James Tonks and Henry Lamont. They were in a shed – not even that, a cupboard – with a bench and a squat rack which we borrowed. We used to go in there at 6.15am. Now, we have an S&C coach. That’s how it all evolved. You still have the 6.15am start but it all started, particularly in rugby, with four boys and it just expanded.”

At those higher levels, rugby remains Cranleigh’s sporting pièce de resistance. And, while success with the oval ball is no longer the direct remit of Houston, he remains fondly attached. He built Cranleigh up from relative also-rans on the school rugby circuit and turned them into the behemoth that they are today. “It’s really been a mindset change. It’s more that we go to things now with the idea of winning it, rather than just being happy to play in a quarter-final. The kids are much more aspirational,” Houston says of that transformation. “When I first started, there was no strength and conditioning as such. There was a group of four boys: Henry Taylor [Northampton Saints], Harry Elrington [London Irish], James Tonks and Henry Lamont. They were in a shed – not even that, a cupboard – with a bench and a squat rack which we borrowed. We used to go in there at 6.15am. Now, we have an S&C coach. That’s how it all evolved. You still have the 6.15am start but it all started, particularly in rugby, with four boys and it just expanded.”

Houston admits that Cranleigh’s rugby facilities, lacking in floodlights, are “not that great”, but he recognises that a perceived lack of material luxuries is no excuse for not reaching the top. “As much as Cranleigh looks like Hogwarts, if you look at the sports facilities and compare us to other schools, our budget is far less,” he says. “So it’s not just about the £39,000 [a year fees]. That money goes into all other parts of school life. Sometimes, people get transfixed on the idea that, if you have the shiniest centre, it makes you good. We’d turn up to a match and I would be there on my own. One of the injured kids would be on the video, and I would do the video analysis. I would strap the kids, coach the kids. That’s us. But we go at it and we do it properly.”

And what of the pupils themselves – isn’t that what it is all about? There is a spread of talent, boys and girls, across a range of sports – rugby, wheelchair tennis, hockey, netball, showjumping and cricket. Some are internationals already and some will be in the future.

After a pre-lockdown visit to the school, I ask them to write, anonymously and in confidence, four words that sum up sport at Cranleigh. The two words that featured across the majority of submissions? Inclusivity and teamwork. That says it all.